Computer software development is a multifaceted process that has evolved continuously with new tools, architectures, and technical expectations. AI-assisted coding and cloud-native platforms have reduced friction, but they don’t replace the underlying work of designing resilient systems, managing integrations, handling scale, or meeting security and compliance requirements.

If you’re preparing to build or modernize software, the process can feel heavy because every phase forces trade-offs that impact architecture, performance characteristics, hiring requirements, and long-term maintainability.

This guide breaks down those stages the way experienced engineering teams approach them, highlighting the practical considerations, common pitfalls, and architectural choices that truly shape outcomes.

Key Takeaways

- Clear requirements and feasibility checks define the system’s limits early: expected load, compliance rules, integration points, stack capability, and operational constraints that shape all later decisions.

- System design fixes the core architecture, including data models, API contracts, communication patterns, scalability approach, observability setup, and security baselines that determine how the software behaves in production.

- Different software types and development disciplines require different runtime environments and delivery workflows, affecting how teams structure services, test components, and manage deployments.

- A functioning SDLC depends on integrated automation across build, testing, and deployment, with CI/CD pipelines, versioning strategy, IaC, and rollout controls ensuring predictable releases.

- Post-launch work, including monitoring, alerting, patching, dependency updates, performance tuning, and cost management, keeps the system stable and prevents reliability issues from accumulating over time.

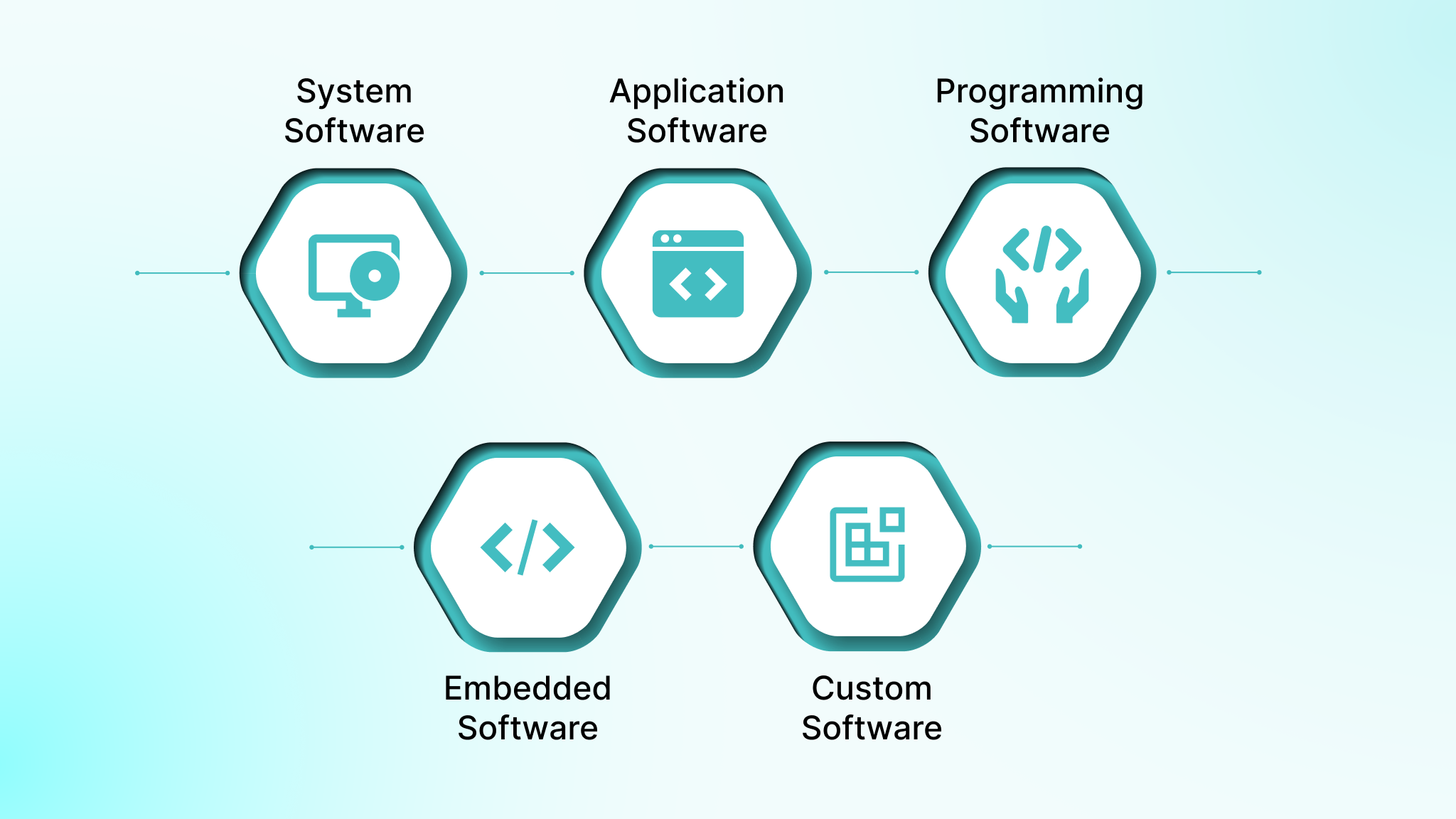

Core Software Types That Shape Modern Engineering Decisions

Software falls into several foundational categories that shape architectural decisions, integration requirements, deployment environments, and long-term maintenance. Each category has its own runtime characteristics, tooling needs, and operational considerations, which influence how the software is designed and delivered.

System Software

System-level programs that manage hardware, operating environments, and core compute resources. Examples include operating systems like Linux and Windows, device drivers, container runtimes, hypervisors, and system utilities used for resource management.

Application Software

End-user or business-facing software that delivers functional workflows. Examples include CRM platforms, ERP systems, productivity tools, and custom web or mobile applications used for internal operations or consumer-facing services.

Programming Software

Tools used by developers to write, test, and maintain code. Examples include compilers, interpreters, build systems, debuggers, and IDEs such as IntelliJ or VS Code.

Embedded Software

Software running inside specialized or resource-constrained devices, often with real-time requirements. Examples include firmware for IoT sensors, automotive control units, medical devices, robotics controllers, and industrial automation systems.

Commercial vs Custom Software

Commercial off-the-shelf software serves broad use cases, while custom-built software targets specific business workflows. Examples include off-the-shelf accounting systems versus a domain-specific platform engineered for regulated environments like healthcare or fintech.

Major Software Development Approaches Across Today’s Tech Stacks

As software ecosystems have matured, software development has fragmented into specialized disciplines, each optimized for different layers of the stack and different functional outcomes.

Choosing the right approach matters because every type influences how teams structure services, test components, deploy changes, and manage long-term maintenance. The list below highlights the categories most relevant to modern product and platform teams.

1. Cloud-Native Development

Cloud-native work focuses on building applications designed to run in elastic, distributed environments from day one. It emphasizes resilience, observability, and automated operations.

Teams typically use:

- Microservices running in containers.

- Orchestration platforms like Kubernetes or ECS.

- Infrastructure as code for environment parity.

- Event-driven architectures and managed cloud services.

This approach is common when teams expect unpredictable scale, multi-region deployments, or frequent releases.

2. Front-End Development

Front-end teams build the client interface that users interact with. The work is not just UI, as it affects API design, caching strategy, and performance budgets.

Technical considerations include:

- Frameworks such as React, Vue, or Angular.

- State-management patterns and component reuse.

- Accessibility, rendering strategy, and page-load performance.

- Alignment with backend API contracts.

Poor front-end design can push unnecessary complexity into backend services, so the two must evolve together.

3. Back-End Development

Back-end engineering, also known as Database Development, focuses on the logic, services, and data layers that power the application. These systems must be reliable, high-performing, and easy to instrument for production debugging.

Typical elements include:

- API design (REST, GraphQL, gRPC).

- Database and storage architecture (SQL, NoSQL, streams).

- Authentication, authorization, and encryption models.

- Concurrency control, caching, and system resilience.

This is where most operational risk lives, especially in high-traffic or regulated systems.

4. Full-Stack Development

Full-stack development refers to engineers who work across the presentation layer, application logic, and data access layers. The role is more about enabling tighter alignment between frontend behavior, API design, and backend data models.

When used effectively, full-stack engineering reduces coordination overhead, accelerates feature delivery, and improves consistency across layers.

Teams rely on full-stack engineers to:

- Design API contracts that fit client workflow constraints.

- Understand how UI rendering, caching, and state management influence backend load.

- Implement end-to-end features without handoffs that introduce latency or misinterpretation.

- Ensure observability and debugging work across the entire request path.

Full-stack development is especially effective in cross-functional squads or early-stage products where rapid iteration and minimal context switching matter.

5. Low-Code and No-Code Development

Low-code and no-code platforms accelerate delivery by providing visual builders, pre-defined components, and managed infrastructure. They are effective for internal applications, workflow digitization, and scenarios where speed matters more than deep customization.

Engineering teams evaluate these platforms based on:

- Integration depth and API extensibility.

- Vendor lock-in and long-term maintainability.

- Data residency, access controls, and compliance alignment.

- Versioning, environment separation, and rollback mechanisms.

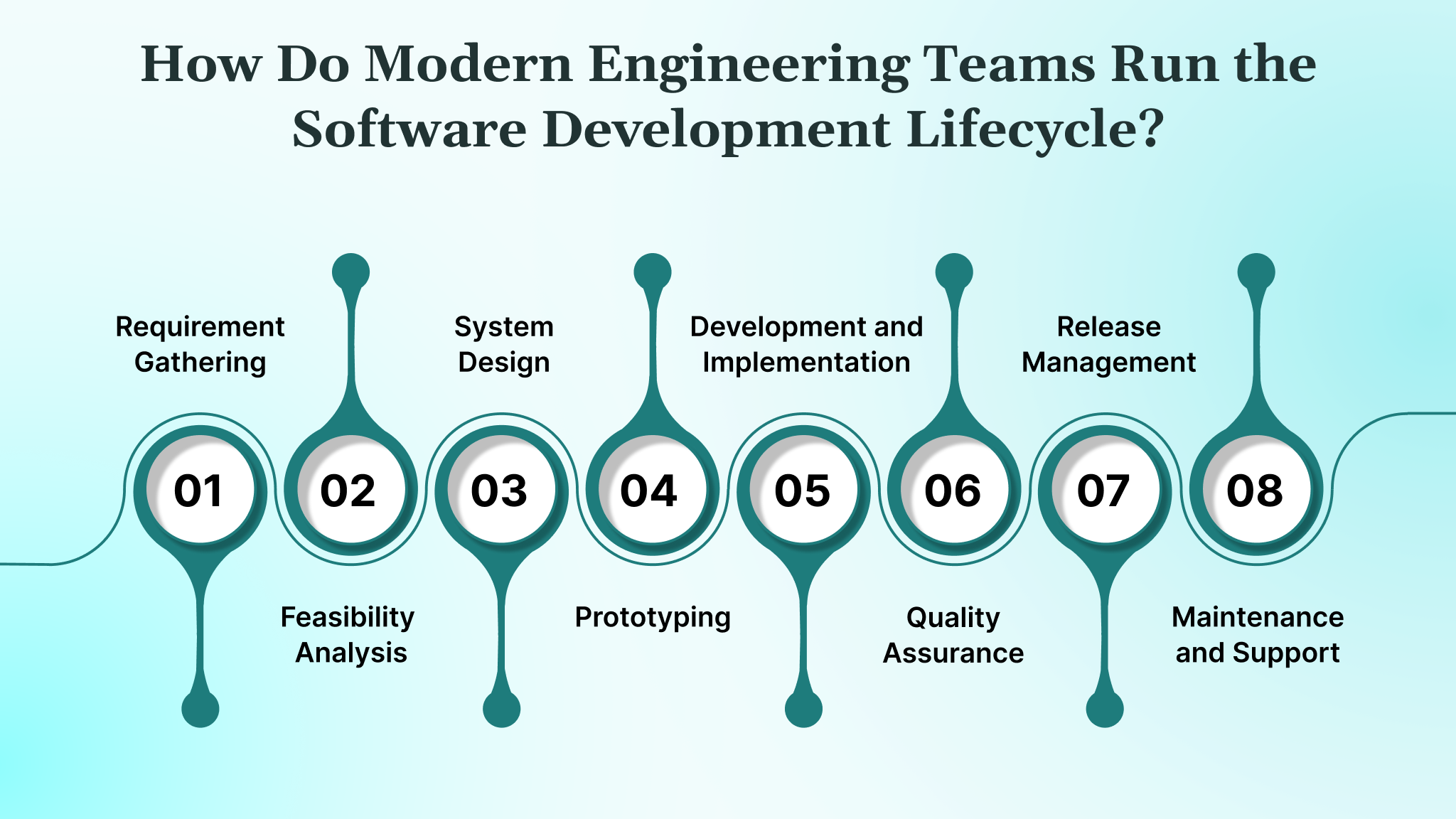

How Do Modern Engineering Teams Run the Software Development Lifecycle?

Modern computer software development follows a lifecycle that looks linear on paper but is anything but linear in practice. High-performing engineering orgs run these phases in parallel, automate most repetitive work through CI/CD, and rely on observability, IaC, and DevOps practices to keep quality high and cycle times predictable.

Whether you’re building net-new systems, modernizing legacy platforms, or scaling a multi-service ecosystem, the SDLC exists to help you:

- Control technical risk early.

- Align architecture with business constraints.

- Maintain delivery velocity without breaking production.

Below is a breakdown of the SDLC steps as they happen in real development environments.

1. Requirement Gathering

Requirement gathering is where engineering leaders define the operational, technical, and regulatory constraints the system must succeed within. At this stage, teams clarify business objectives, identify edge cases early, and translate broad expectations into specifications that can drive architecture, infrastructure planning, and delivery timelines.

When done well, this phase eliminates ambiguity and prevents downstream engineering rework.

To make this phase actionable, high-performing teams focus on:

- Capturing both functional and non-functional requirements (latency budgets, peak loads, concurrency expectations, security constraints, compliance rules, data retention, auditability). These shape architectural choices long before development begins.

- Mapping real-world workflows using event storming, domain-driven design (DDD) techniques, and user journey modeling to uncover hidden dependencies and operational edge cases.

- Defining acceptance criteria and technical success measures, including SLOs, throughput expectations, integration boundaries, and error-handling rules to ensure all stakeholders share a single definition of “done.”

- Documenting risks and unknowns early, including feature ambiguity, missing data sources, external dependencies, or compliance blockers, so they can be resolved before the architecture is finalized.

This combination of structured discovery and technical rigor ensures that requirements become a reliable blueprint and reduces costly misalignment during later development stages.

2. Feasibility Analysis

In this phase, engineering leaders assess whether the proposed solution can be delivered realistically, given the team’s skills, architectural maturity, budget, infrastructure, compliance obligations, and delivery timeline.

High-performing teams evaluate feasibility in four dimensions:

- Technical feasibility examines legacy system constraints, integration boundaries, expected traffic profiles, compliance requirements, and operational complexity.

- Financial feasibility measures the actual cost of ownership. Teams account for cloud compute and storage, networking, managed service tiers, observability tools, vendor licensing, support overhead, and security review cycles.

- Operational feasibility evaluates whether the system can be supported by your existing team. If the architecture requires Kubernetes, service mesh, distributed tracing, and a strong SRE culture, but the team has never operated such a stack, the feasibility score changes dramatically.

- Risk assessment highlights integration blockers, migration complexity, dependency volatility, performance uncertainty, and single points of failure.

A credible feasibility review protects teams from walking into avoidable rebuilds and ensures that the final architecture aligns with what the organization can actually support.

3. System Design

System design converts requirements into a concrete architecture. This phase determines how the system scales, how it fails, how it is secured, and how expensive it will be to evolve. Most long-term cost is set here, which is why senior engineers treat design decisions as strategic commitments rather than technical preferences.

Key areas of focus include:

- Architectural patterns such as modular monolith vs microservices, event-driven designs, request-response flows, gRPC vs REST, message brokers, caching layers, and failover strategies. Each choice affects latency, complexity, scalability, and operability.

- UI and UX design clarifies information architecture, workflow expectations, accessibility requirements, and how the front end influences backend load and API design.

- Technology stack selection prioritizes stability and team capability over trends. Team evaluates ecosystem maturity, hiring feasibility, operational overhead, performance characteristics, and long-term compatibility with the broader platform.

- Design artifacts include architecture diagrams, ERDs, API contracts with versioning guidance, data flow documentation, security baselines, and observability plans that define what will be measured and how incidents will be diagnosed.

4. Prototyping

Prototyping is a controlled risk-reduction step. It replaces speculation with evidence by validating high-impact assumptions before full implementation. It is a targeted exploration meant to reveal technical and product uncertainties early.

CTOs and engineering teams rely on prototypes to test:

- Behavior under edge cases, especially flows that are hard to predict from documentation alone.

- Integration feasibility with third-party APIs, legacy systems, or internal services whose reliability and response patterns need verification.

- User workflow friction, ensuring that the intended experience matches real user expectations and operational realities.

- Data model adequacy, especially for domains where relationships, cardinality, or mutation rules need early validation.

- Architectural viability, where evolutionary prototypes double as technical spikes to test performance limits, concurrency behavior, or infrastructure choices.

5. Development and Implementation

This is where architecture becomes working software. Modern engineering teams focus on code quality, maintainability, and production readiness from the start.

Teams emphasize:

- Coding standards that enforce clarity, modularity, and predictable structure. This reduces onboarding time and technical debt.

- Version control workflows, such as trunk-based development or GitFlow, are chosen based on release frequency and coordination requirements.

- CI pipelines that run static analysis, security checks, dependency scans, unit tests, and integration tests before allowing merges. This is how teams maintain stability without slowing development.

- Integration work, including API contracts, service orchestration, caching, messaging, schema migrations, and environment configuration. Advanced features like feature flags and circuit breakers support controlled rollouts and resilience.

6. Testing and Quality Assurance

Quality assurance is integrated into the build process so issues surface at the point of change rather than at the point of release. This protects delivery timelines and reduces rework later in the cycle.

Testing includes:

- Unit tests that validate core logic with high coverage across critical functions.

- Integration tests that verify communication across services using mocks or real subsystems based on complexity and reliability requirements.

- Performance and load testing to validate concurrency behavior, latency budgets, and scalability assumptions.

- Security testing, including static analysis, dynamic scans, dependency checks, and permission modeling.

- Regression suites are automated within CI/CD to ensure that new changes do not break existing functionality.

7. Deployment and Release Management

Deployment is where engineering meets operational reality. Mature organizations automate the full release path to minimize human error and ensure repeatability across environments.

Teams focus on:

- Infrastructure-as-Code to provision consistent environments across dev, staging, and prod. This makes environments reproducible and reduces configuration drift.

- Secrets and configuration management through Vault, AWS Secrets Manager, or cloud-native solutions to prevent insecure handling of sensitive data.

- Automated pipelines that manage build artifacts, run smoke tests, migrate databases, and validate system readiness.

- Release strategies such as canary, rolling, or blue-green deployments that allow gradual exposure and instant rollback when anomalies appear.

- Observability during rollout, monitoring latency, error rates, saturation, and downstream impacts using tools like Prometheus, Grafana, Datadog, or OpenTelemetry.

A disciplined release process ensures deployments are routine and low risk, even in high-traffic or highly regulated environments.

8. Maintenance and Support

Once software is in production, maintenance becomes the backbone of reliability. This phase keeps the system secure, performant, and aligned with evolving business needs. The work is continuous and heavily operational.

Teams maintain reliability through:

- Monitoring golden signals such as latency, traffic, errors, and resource saturation to detect issues early.

- Automated alerting based on defined SLOs to prevent unnoticed degradation.

- Patch management for security vulnerabilities, dependency updates, and infrastructure improvements.

- Performance optimizations, including query tuning, caching refinements, load distribution, and cost optimization across cloud resources.

- Feature evolution, driven by product priorities, user analytics, and technical opportunities uncovered through ongoing monitoring.

Software Development Models Used in Modern Engineering

Different projects require different delivery structures. The software development methodologies below reflect how teams organize sequencing, validation, feedback loops, and risk management. Each model has strengths and trade-offs depending on regulatory pressure, system complexity, integration depth, and release cadence.

- Waterfall: A linear, phase-by-phase model suited for projects with tightly defined, stable requirements. Common in regulated environments where documentation and traceability are mandatory.

- Agile: An iterative approach that breaks work into short cycles. Effective when requirements evolve, when teams need fast feedback, and when cross-functional squads manage work collaboratively.

- Iterative: Builds the system in repeated cycles, adding or refining functionality each time. Used when teams need early working versions before the complete architecture is finalized.

- DevOps: A delivery model that integrates development and operations to automate builds, testing, and deployments. Best for teams shipping frequently, requiring observability, CI/CD pipelines, and predictable releases.

- Spiral: Combines linear planning with iterative cycles, adding structured risk analysis at each loop. Useful for large, complex systems where unknowns must be validated before major investment.

- Rapid Application Development (RAD): Focuses on fast prototyping and continuous user involvement. Works well for UI-heavy applications or when stakeholders need to interact with early versions to clarify requirements.

- Lean: A process that emphasizes removing waste, shortening feedback loops, and simplifying decision-making. Often adopted by teams prioritizing speed and operational efficiency, with minimal process overhead.

- V-Model: An extension of the Waterfall model that pairs each development phase with a corresponding test phase. Used when teams need high assurance and traceable verification, such as medical or aerospace systems.

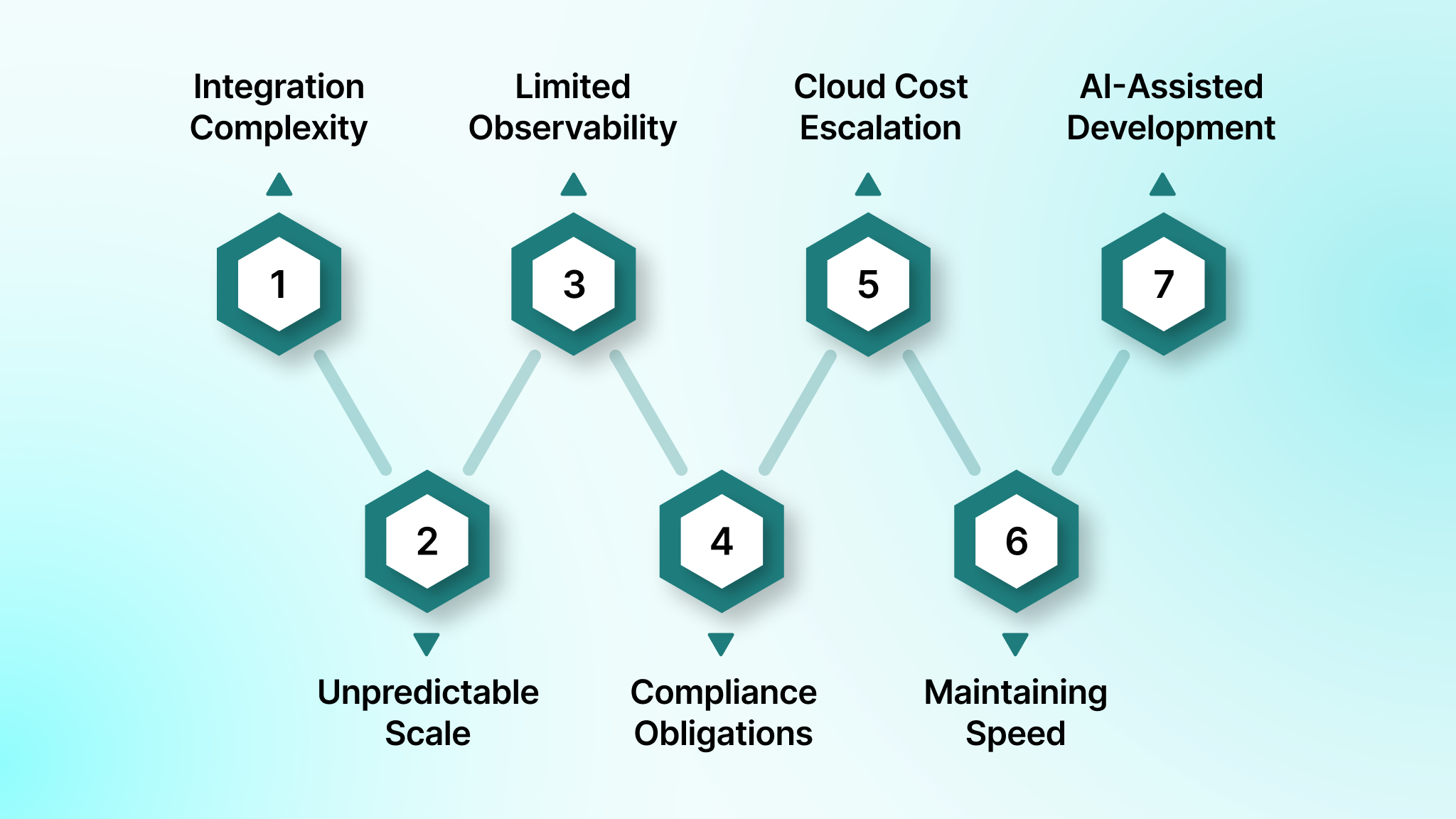

Key Challenges in Modern Software Development (and How You Can Address Them)

Modern engineering teams operate under constraints that are far more complex than classic SDLC diagrams suggest. Distributed systems, compliance-heavy environments, multi-cloud footprints, and AI-driven development workflows introduce new risks that traditional methodologies were never designed to handle.

The challenges below represent the most common sources of delivery friction and how you can mitigate them.

Integration Complexity Across Services

- Distributed systems often fail at the boundaries where payload inconsistencies, undocumented behavior, and mismatched timeout rules only appear under real traffic.

- You can enforce API contracts, apply consistent timeout and retry policies, and use distributed tracing with correlation IDs to locate failures quickly.

Unpredictable Scale and Performance Pressure

- Traffic bursts expose bottlenecks in queues, caches, and databases. Systems that run well at baseline may degrade quickly under concurrency spikes.

- You can run load and stress tests early, tie autoscaling thresholds to SLOs, and build backpressure into services to prevent resource saturation.

Limited Observability During Incidents

- Logs alone cannot explain behavior across multiple services, and teams lose time reconstructing workflows because metrics and traces are inconsistent or incomplete.

- You can standardize instrumentation with common telemetry libraries and build dashboards based on user-facing performance.

Security and Compliance Obligations

- Each new service introduces additional identities, policies, and data flows. Misconfigurations or outdated dependencies increase exposure and create audit challenges.

- You can integrate automated scans into CI, maintain a dependency inventory, and verify permissions at each service boundary.

Cloud Cost Escalation

- Cloud-native systems generate costs quickly through idle resources, excessive microservices, and high network usage, often visible only during billing cycles.

- You can add cost dashboards, configure consumption alerts, and review architecture choices that create unnecessary compute, storage, or network churn.

Maintaining Speed Without Degrading Reliability

- Rapid delivery introduces risk when tests, reviews, and rollbacks are inconsistent, and outages slow teams down over time.

- You can adopt trunk-based development supported by automated tests, feature flags, and reliable rollback paths.

Quality Drift From AI-Assisted Development

- AI speeds up coding but may introduce insecure patterns, inconsistent logic, or code that does not align with your architecture standards.

- You can review generated code, apply automated security and quality scans, and set internal guidelines for when and how AI tools should be used.

How DEVtrust Helps You Build Software That Holds Up in Production

If you’re planning to build or modernize software, the practices covered in this guide are the same principles we apply at DEVtrust in real engineering environments. Our teams work with you from the start to define constraints, validate feasibility, and align every architectural decision with your operational reality.

We support your project across every stage of the lifecycle:

- Requirements and Feasibility: We map domain events, clarify NFRs, assess integration boundaries, and validate whether your team, budget, and stack can realistically support the system before development begins.

- Architecture and System Design: We design data models, API contracts, communication patterns, observability plans, and security baselines that keep your platform reliable under real traffic.

- Development Across All Technical Disciplines: We build with the tooling and workflows appropriate to your environment and regulatory context, including cloud-native services, front-end systems, backend logic, full-stack features, or low-code extensions.

- End-to-End Delivery Automation: We implement CI/CD pipelines, contract tests, IaC, environment strategy, and controlled rollout processes so releases are predictable and low-risk.

- Production Stability and Continuous Improvement: We set up monitoring, alerting, patching workflows, cost controls, and performance tuning to keep the system stable long after launch.

If you need a partner who can guide the technical decisions and execute the build with production-grade discipline, DEVtrust is built for that level of work.

Conclusion

Developing software requires careful planning, attention to detail, and ongoing collaboration. From gathering requirements to post-deployment support, each phase contributes to the project’s success. By following best practices and leveraging the right tools, businesses can develop software that meets both user needs and business objectives.